On pain and “the suffering of suffering”

“don’t reject thoughts, since they are the play of your innate nature. Don’t reject disturbing emotions, since they are the reminders of wisdom. Don’t reject sickness and suffering, since they are your spiritual friends” -from The Precious Garland of the Sublime Path Lord Gampopa (trans Kunsang)

“whatever you resist, persists”

-Carl Jung

We have a very particular relationship to our human pain and suffering: we instinctively don’t like it, recoil from it and we engage in many different ways to remove it from our experience. We have an aversion to our pain and suffering and over time chronic pain can lead us to depression and despair. Suffering includes our sadness, sorrows, losses, our dissatisfaction with work, family, relationships-I use suffering in its wider aspect here, closer to what the Buddhists call “dukkha” which can be nearer to a kind of existential uncertainty as well as an outright pain.

We meet our emotional and physical pain often with resistance, a resistance which builds into a narrative, an account or story of our suffering, a story about ourselves or the world.

So, in our pain and suffering we reach for a pain killer, or find ways to suppress difficult thoughts and emotions, perhaps drowning our experience of suffering in addiction or distractions, from gaming to alcohol abuse. In every event, we are perhaps fighting off a very human experience, splitting off or suppressing a significant part of us that makes us human.

And it probably doesn’t work.

There’s an emotional and physical tensing in our resistance, a kind of contraction sometimes called an egoic contraction that fixates around the pain and results in a turning away which, ironically, makes the pain worse.

Killing off or suppressing our suffering will probably not make our suffering vanish; at best it will mask it or encourage it to be channelled into surprising-and at times quite awful symptoms, such as resentment, bitterness, anger, or physical complaints such as eczema.

We are required to face and engage with our suffering or be not-so-subtly led by the “suffering of our suffering” so to speak. Significantly, we are bound up in unnecessary suffering in our resistance to pain, so we layer our suffering with more suffering, creating and sustaining stories of resentment, blame, a desire to hurt those who we believe hurt us, yet the hurt often was long ago delivered, but still carried by our storied selves and becomes as wise in its behaviour as throwing gasoline onto a fire in order to put it out.

There is another way to relate to our suffering.

To begin with, we need to view our suffering in a radically different light, from an experience to be disowned and banished to one that we can find meaning, insight and wisdom in, one that we can find a powerful sense of human connection in. Given that the whole population of this planet will experience pain and suffering, this would appear to be of critical importance.

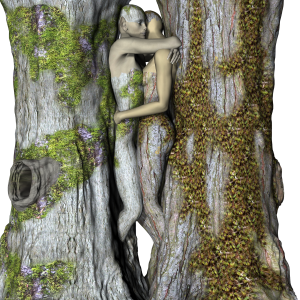

Our pain and suffering are ours, is “me”, an integral part of what it is to be human, vulnerable, interconnected to the planet’s populous; we are connected, you and I in our suffering selves. It is important to consider how we might approach mindfully and bear our pain and suffering, how the tears and sorrow inherent in our messy humanity enriches the complexity of our soul and the compassion in our hearts, finding new connections to parts of ourselves we had disowned, reaching out to others in kinship. You are my family, you are my sister and brother, for we suffer all-this is a step towards “wholing,” finding and connecting with the difficult parts of ourselves that hurt, that are wounded, and caring for them, not rejecting them.

This cannot be done without meeting and engaging with our wounds, yet how to do this without recoiling more, for in turning towards our suffering, might we feel more pain rather than less? Why would anybody in their right mind do this?

We can soften into our suffering, experiencing it as energy, sensation and noticing the change in the pattern and tone of these sensations, their impermanence. Doing this, we are turning back to pain itself and away from suffering, back to the primary sensation rather than the secondary stories of resistance we have carried for so long in our wounded hearts. Bringing awareness to suffering, coming back to that awareness, to the pain, is a radical act of mindfulness and tender healing love for the self.

So we can turn towards our suffering as we would turn towards a child in pain, turning to it with compassion and awareness, asking our suffering what it needs and what teaching it is bringing to us, for it is. This might take time, but surely is worthwhile, for it further strips way the “suffering of our suffering” the layer that we put on our pain and suffering in a bid to resist that takes us away from the experience and makes it much worse; ironically perhaps making it more permanent and less impermanent. This gives us an opportunity to both wake up and grow up (for this is what our suffering is calling us to do) into a fuller range of being that stays with the pain. A more mature self will find a capacity to carry and contain pain and suffering without the need to split it off, suppress it or project it onto others, and find a way to own the primary pain.

We all want to be happy, but focussing on happiness while rejecting pain and suffering is to believe a coin has only one side and deny the existence of other side; this does not mean it goes away, it just works its way in the dark where we are blind to it. An aversion and a resistance to pain and suffering is an aversion and a resistance to life itself, and hence a life not fully lived.